Problem Statement

Origin Korean drama Melancholia, Episode 2. Refer to the previous episode for the plot. Depending on your region, you might be able to watch the episode for free on Rakuten Viki. Spoilers ahead.

After the event in Episode 1, Ji Yoon-soo confronts Baek Seung-yoo about the placement test, but Seung-yoo continues to deny his interest in math. In an attempt to respark Seung-yoo's passion, Yoon-soo gives him the following problem:

When $n$ points are randomly chosen in the interior of a circle, find the probability that these points are the vertices of a convex $n$-gon (where $n \geq 4$).

(The points are independently and uniformly random in the Cartesian coordinates.) The problem is tricky enough to become a plot point for many subsequent episodes. As a starter, try solving the $n = 4$ case first.

$\gdef\ex#1{\operatorname{\mathbb{E}}\left( #1 \right)}$ $\gdef\exr#1{\operatorname{\mathbb{E}'}\left( #1 \right)}$

Solutions when $n = 4$

The problem is a generalization of the classical Sylvester's Four-Point Problem from 1865: compute the probability that 4 points randomly chosen in the given region form a convex quadrilateral. Our region of interest is a disk (i.e., interior of a circle). This 4-points-in-a-disk version was also featured in Putnam 2006 as problem A6 (aka the hardest problem of day 1).

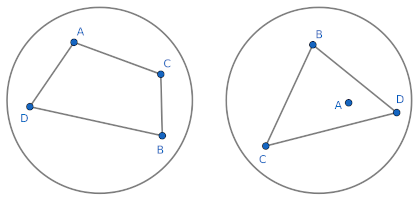

Let our region be a disk of radius 1 centered at the origin $O$, and let the points be $A, B, C, D$. Almost surely, either the points form a convex quadrilateral, or one of the points is inside the triangle formed by the others. So the probability we want is

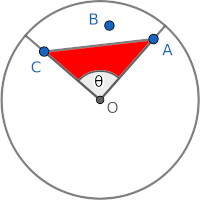

$$\begin{aligned} \text{answer} &= 1 - \prob{A \in \triangle BCD} - \prob{B \in \triangle ACD} - \prob{C \in \triangle ABD} - \prob{D \in \triangle ABC} \\ &= 1 - 4\prob{D\in \triangle ABC} \qquad \text{(due to symmetry)} \\ &= 1 - 4\frac{\ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}}}{\pi \times 1^2} \end{aligned}$$where $\crab{\dots}$ denotes the area, and the expectation is taken over $A,B,C$ uniformly distributed in the disk. The problem thus reduces to finding the average area of random triangles inside a unit disk.

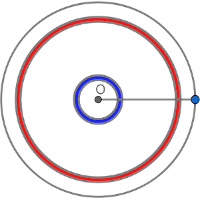

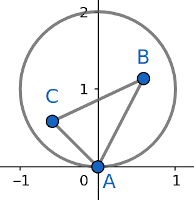

There are multiple ways to compute this average. But before we proceed, here's a caution regarding the probability density. Let our points in the Cartesian coordinates be $(X, Y)$ where $X$ and $Y$ are random variables. If we switch to polar coordinates $(R, \Theta)$ where $(X, Y) = (R\cos\Theta, R\sin\Theta)$, the distribution of $R$ is not uniform: there are more points with large $R = r$ than points with small $R = r$.

Note that $R$ and $\Theta$ are independent and $\Theta$ is uniform ($f(\theta) = 1/2\pi$). The probability that $R$ falls inside the range $[r, r + dr]$ (as colored above) is $\frac{2\pi r\,dr}{\pi\times 1^2} = 2r\,dr$, meaning the probability density function of $R$ is $f(r) = 2r$ for $r \in [0, 1]$. One could also take the derivative of the cumulative density $F(r) = \prob{R < r} = \frac{\pi r^2}{\pi\times 1^2} = r^2$ to get $f(r) = 2r$.

A more general method for computing the change in the density function is to write the Jacobian:

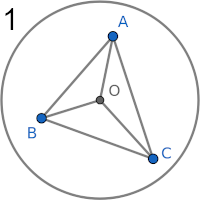

$$\begin{aligned} f(r,\theta) &= f(x,y)\begin{vmatrix} \fracp{x}{r} & \fracp{x}{\theta} \\ \fracp{y}{r} & \fracp{y}{\theta} \end{vmatrix} \\ &= f(x,y)\begin{vmatrix} \cos\theta & -r \sin\theta \\ \sin\theta & r \cos\theta \end{vmatrix} \\ &= f(x,y)\,r \end{aligned}$$Solution 1: Look at $\crab{\triangle OAB}$, $\crab{\triangle OBC}$, $\crab{\triangle OCA}$

This solution is by Daniel Kane (ref1, ref2).

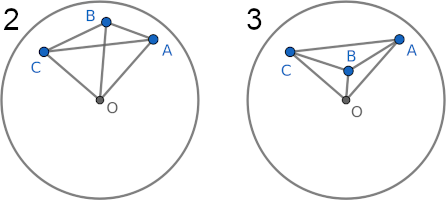

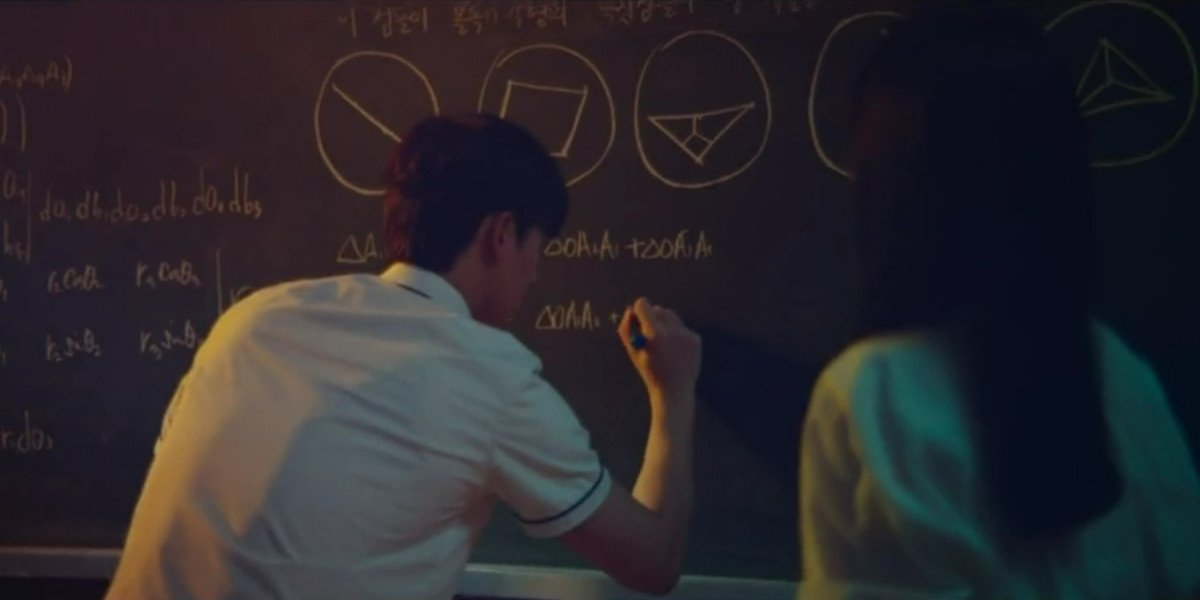

Draw $OA$, $OB$, and $OC$. We have 3 cases as pictured above. Cases 2 and 3 happen when $A,B,C$ lie on the same semicircle, and WLOG we let $B$ lie in the middle. We have

$$\crab{\triangle ABC} = \cases{ +\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} + \crab{\triangle OCA} & \text{for case 1} \\ +\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} - \crab{\triangle OCA} & \text{for case 2} \\ -\crab{\triangle OAB} - \crab{\triangle OBC} + \crab{\triangle OCA} & \text{for case 3} \\ }$$Our plan is to first compute the main term $\ex{+\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} + \crab{\triangle OCA}}$ while ignoring of the cases, and then subtract correction terms for cases 2 and 3.

The main term

Let's compute $\ex{+\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} + \crab{\triangle OCA}}$. Due to symmetry, we can just find $\ex{\crab{\triangle OAB}}$ then multiply by 3. We demonstrate two ways to compute $\ex{\crab{\triangle OAB}}$.

Method 1 Let $r_1 = OA$, $r_2 = OB$, and $\theta = \angle AOB$. Due to symmetry, we can limit $\theta \in [0, \pi]$. The corresponding random variables $R_1$, $R_2$ and $\Theta$ are independent, and their probability density functions are $2r_1$, $2r_2$, and $1/\pi$. So

$$\begin{aligned} \ex{\crab{\triangle OAB}} &= \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^1 \nail{\frac{1}{2}r_1 r_2 \sin\theta}\,\frac{2r_1 2r_2}{\pi}\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta \\ &= \frac{2}{\pi}\nail{\int_0^{\pi}\sin\theta\,d\theta}\nail{\int_0^1 r_1^2\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^1 r_2^2\,dr_2} \\ &= \frac{2}{\pi}\nail{2}\nail{\frac{1}{3}}\nail{\frac{1}{3}} = \frac{4}{9\pi} \end{aligned}$$This means $\ex{+\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} + \crab{\triangle OCA}} = \frac{4}{3\pi}$.

Method 2 If we don't want to reason with independence and probability distributions and whatnot, we can apply the Jacobian and do the full integral. Let $A = (r_1, \theta_1)$ and $B = (r_2, \theta_2)$. Then

$$\begin{aligned} \ex{\crab{\triangle OAB}} &= \frac{\int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^1 \nail{\frac{1}{2}r_1 r_2 \sin\abs{\theta_1-\theta_2}}\,r_1r_2\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2} {\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^1 \nail{1}\,r_1r_2\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2} \\ &= \frac{\frac{1}{2}\nail{\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{2\pi} \sin\abs{\theta_1 - \theta_2}\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2}\nail{\int_0^1 r_1^2\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^1 r_2^2\,dr_2}} {\nail{\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta_1}\nail{\int_0^{2\pi} d\theta_2}\nail{\int_0^1 r_1\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^1 r_2\,dr_2}} \\ &= \frac{\frac{1}{2}\nail{2\pi\times 4}\nail{\frac{1}{3}}\nail{\frac{1}{3}}} {\nail{2\pi}\nail{2\pi}\nail{\frac{1}{2}}\nail{\frac{1}{2}}} = \frac{4}{9\pi} \end{aligned}$$which gives the same final answer $\frac{4}{3\pi}$. The expectation is conditioning on the points being in the disk, hence the denominator. The term $2\pi \times 4$ comes from the fact that for any $\theta_2 \in [0, 2\pi]$, the graph $\sin\abs{\theta_1 - \theta_2}$ where $\theta_1 \in [0, 2\pi]$ will amount to 2 peaks of the sine wave, which have the area under curve of 4.

The correction terms

The main term over-counts some sub-triangles when case 2 or 3 occurs. The correction terms we need are

$$\begin{aligned} &-2\times \prob{\text{case 2}}\ex{\crab{\triangle OCA} \mid \text{case 2}} \\ &-2\times \prob{\text{case 3}}\ex{\crab{\triangle OAB} + \crab{\triangle OBC} \mid \text{case 3}} \end{aligned}$$To make things simpler, let's merge cases 2 and 3 by introducing an indicator $\chi = \II[B \in \triangle OAC]$ (= 0 for case 2; = 1 for case 3). Also note that $\ex{\crab{\triangle OAB}\mid \dots} = \ex{\crab{\triangle OBC}\mid\dots}$ due to symmetry. The correction terms become

$$ -2\times \prob{\text{case 2 or 3}}\ex{(1-\chi)\crab{\triangle OCA} + 2\chi\crab{\triangle OAB} \mid \text{case 2 or 3}} $$Write $\exr{\ldots} = \ex{\ldots \mid \text{case 2 or 3}}$. Let's deal with each of these terms.

The probability $\prob{\text{case 2 or 3}}$ What's the probability that case 2 or 3 (i.e., $O \not\in \triangle ABC$) occurs? This is yet another classic problem. As explained in this 3Blue1Brown video, we can reorder the point sampling process as:

- Sample $A$ in the disk.

- Sample two diameters $d_B$ and $d_C$.

- Sample $B \in d_B$ and $C \in d_C$.

One needs to pick the right half of both $d_B$ and $d_C$ to get $O \in \triangle ABC$, so the chance of $O \not\in\triangle ABC$ is $3/4$.

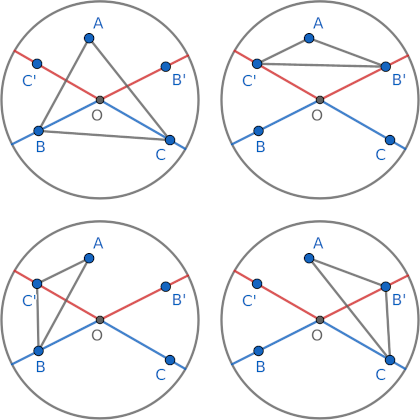

The expectation $\exr{(1 - \chi)\crab{\triangle OCA}}$ We compute $\exr{\crab{\triangle OCA}}$ and $\exr{\chi\crab{\triangle OCA}}$ separately. Let's bring back the figures.

The radii for $A$ and $C$ still have distributions $2r$. The angle $\theta := \angle AOC$ has distribution $2\theta/\pi^2$ when $\theta \in [0,\pi]$. (Handwavy argument: the density of $\theta$ is proportional to the amount of possible choices for $B$, which is then proportional to the area of the disk sector under angle $\theta$. This area grows linearly with $\theta$, thus the density function is $\theta$ times some constant that would make the total distribution equal 1. That constant is $1/\int_0^\pi \theta\,d\theta = 2/\pi^2$.) So we get

$$\begin{aligned} \exr{\crab{\triangle OCA}} &= \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^1 \nail{\frac{1}{2}r_1 r_2 \sin\theta}\,2r_1 2r_2\frac{2\theta}{\pi^2}\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta \\ &= \frac{4}{\pi^2}\nail{\int_0^{\pi}\theta\sin\theta\,d\theta}\nail{\int_0^1 r_1^2\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^1 r_2^2\,dr_2} \\ &= \frac{4}{\pi^2}\nail{\pi}\nail{\frac{1}{3}}\nail{\frac{1}{3}} = \frac{4}{9\pi} \end{aligned}$$Now comes the neat part: for a given $\triangle OCA$, the probability that $\chi = 1$ (i.e., $B\in\triangle OCA$) is the ratio of $\crab{\triangle OCA}$ to the disk sector under the angle $\theta$.

So we get

$$\begin{aligned} \exr{\chi\crab{\triangle OCA}} &= \exr{\frac{\crab{\triangle OCA}}{\frac{\theta}{2\pi}\times\pi\times 1^2}\crab{\triangle OCA}} \\ &= \int_0^{\pi} \int_0^1 \int_0^1 \frac{2}{\theta}\nail{\frac{1}{2}r_1 r_2 \sin\theta}^2\,2r_1 2r_2\frac{2\theta}{\pi^2}\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta \\ &= \frac{4}{\pi^2}\nail{\int_0^{\pi}\sin^2\theta\,d\theta}\nail{\int_0^1 r_1^3\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^1 r_2^3\,dr_2} \\ &= \frac{4}{\pi^2}\nail{\frac{\pi}{2}}\nail{\frac{1}{4}}\nail{\frac{1}{4}} = \frac{1}{8\pi} \end{aligned}$$The expectation $\exr{\chi\crab{\triangle OAB}}$ Let's first answer the following question: for a given $\triangle OCA$, when $B$ is randomly chosen inside $\triangle OCA$, what's the expected area of $\triangle OAB$?

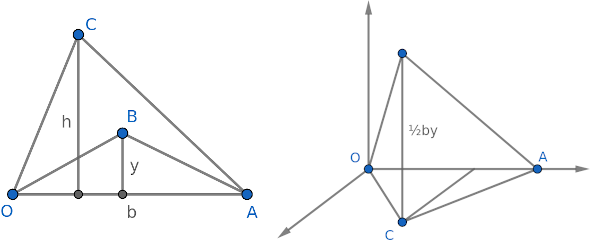

The answer is $\frac{1}{3}\crab{\triangle OCA}$. The papers make it look like a trivial fact but I couldn't find it anywhere. One way to quickly visualize the answer is to put the triangle in the x-y plane and plot $z = \crab{\triangle OAB} = \frac{1}{2}by$. You would get a pyramid with base $\triangle OCA$ and height $\frac{1}{2}bh = \crab{\triangle OCA}$. So the volume is $\frac{1}{3}\crab{\triangle OCA}^2$, and the average of $z$ we wanted is the volume divided by the base area, which is $\frac{1}{3}\crab{\triangle OCA}$.

With this, we get $\exr{\chi\crab{\triangle OAB}} = \frac{1}{3}\exr{\chi\crab{\triangle OCA}} = \frac{1}{24\pi}$.

Combine everything

The correction terms become

$$\begin{aligned} & -2\times \prob{\text{case 2 or 3}}\ex{(1-\chi)\crab{\triangle OCA} + 2\chi\crab{\triangle OAB} \mid \text{case 2 or 3}} \\ &= -2\times\frac{3}{4}\nail{\frac{4}{9\pi} - \frac{1}{8\pi} + 2\times \frac{1}{24\pi}} = -\frac{29}{48\pi} \end{aligned}$$Combining this with the main term gives

$$\ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}} = \frac{4}{3\pi} - \frac{29}{48\pi} = \frac{35}{48\pi}$$And thus the probability that 4 random points in a disk form a convex quadrilateral is

$$1 - 4\times\frac{35/48\pi}{\pi} = 1 - \frac{35}{12\pi^2}$$Before we proceed, here's what happens in Melancholia (Spoilers!):

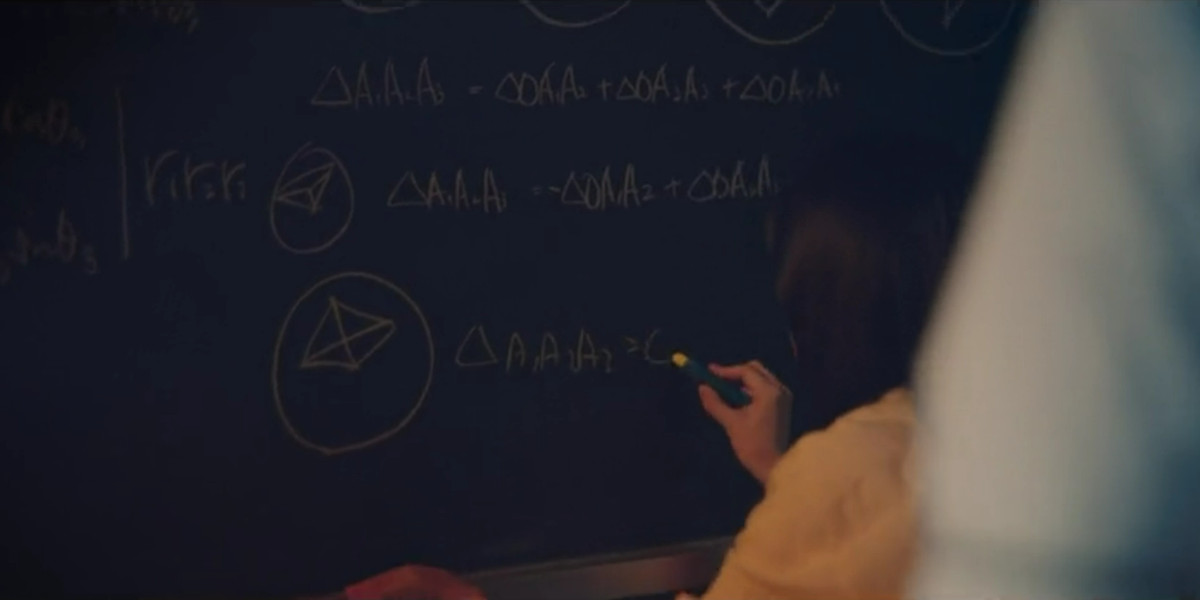

Seung-yoo keeps thinking about the problem. That night, he sneaks into the classroom and begins working on the problem. Yoon-soo notices him and joins in the fun.

The scene is astonishingly realistic. The actors ooze thrill and excitement while solving the problem, the music is vivifying, and what they write on the board actually traces Solution 1. I'm pretty impressed.

Solution 2: Pin one point on the disk boundary

This solution is likely the original solution by W.S.B. Woolhouse back in the 1860s. The Putnam solution is credited to Noam Elkies (ref1, ref2, ref3).

Pin point A on the boundary

We first compute the average of $\crab{\triangle ABC}$ when one point (WLOG, $A$) is on the disk boundary. To do so, we temporarily move the disk so that $A$ is at $(0,0)$ and the center is at $(0, 1)$.

Points in the disk are given by polar coordinates $(r, \theta)$ where $\theta \in [0, \pi]$ and $r \in [0, 2\sin\theta]$. If $B = (r_1, \theta_1)$ and $C = (r_2, \theta_2)$, the value of $\ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}\mid A \in\text{boundary}}$ will be

$$ \frac{\int_0^\pi \int_0^\pi \int_0^{2\sin\theta_1} \int_0^{2\sin\theta_2} \nail{\frac{1}{2}r_1r_2\sin\abs{\theta_1 - \theta_2}}\, r_1r_2\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2} {\int_0^\pi \int_0^\pi \int_0^{2\sin\theta_1} \int_0^{2\sin\theta_2} \nail{1}\, r_1r_2\,dr_1\,dr_2\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2} $$The numerator is

$$\begin{aligned} &= \int_0^\pi \int_0^\pi\crab{\frac{1}{2}\sin\abs{\theta_1 - \theta_2}\nail{\int_0^{2\sin\theta_1}r_1^2\,dr_1}\nail{\int_0^{2\sin\theta_2}r_2^2\,dr_2}}\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2 \\ &= \frac{32}{9}\int_0^\pi \int_0^\pi\crab{\sin\abs{\theta_1 - \theta_2} \sin^3\theta_1 \sin^3\theta_2}\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2 \\ &= \frac{64}{9}\int_0^\pi \int_0^{\theta_1}\crab{\sin(\theta_1 - \theta_2) \sin^3\theta_1 \sin^3\theta_2}\,d\theta_1\,d\theta_2 \qquad \text{(symmetry!)} \\ &= \text{\dots blood and gore (or Wolfram Alpha)\dots} \\ &= \frac{64}{9}\times \frac{35\pi}{256} = \frac{35\pi}{36} \end{aligned}$$And the denominator is

$$\begin{aligned} &= \nail{\int_0^\pi \int_0^{2\sin\theta_1} r_1\,dr_1\,d\theta_1}\nail{\int_0^\pi \int_0^{2\sin\theta_2} r_2\,dr_2\,d\theta_2} \\ &= \nail{\int_0^\pi 2\sin^2\theta_1\,d\theta_1} \nail{\int_0^\pi 2\sin^2\theta_2\,d\theta_2} \\ &= \nail{\pi}\nail{\pi} = \pi^2 \end{aligned}$$So $\ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}\mid A \in\text{boundary}} = \frac{35}{36\pi}$. And if the radius were $q$ instead of 1, we would have $\ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}\mid A \in\text{boundary}} = \frac{35q^2}{36\pi}$.

Unpin the point

There are a few ways to answer the original question based on what we just computed.

Method 1 Define random variable $Q = \max\set{OA, OB, OC}$. The cumulative distribution of $Q$ is

$$F(q) = \prob{OA, OB, OC \leq q} = \nail{\frac{\pi q^2}{\pi\times 1^2}}^3 = q^6$$So the density function is the derivative $f(q) = 6q^5$. We now have

$$\begin{aligned} \ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}} &= \int_0^1 \ex{\crab{\triangle ABC}\mid Q = q} f(q) \,dq \\ &= \int_0^1 \frac{35q^2}{36\pi} 6q^5 \,dq \\ &= \frac{35}{48\pi} \end{aligned}$$And the answer to the original question is $1 - \frac{4}{\pi}\times \frac{35}{48\pi} = 1 - \frac{35}{12\pi^2}$.

Method 2 A more generic method that also works with other types of regions is to apply Crofton's theorem. There are a few theorems named after Crofton (a prominent mathematician on geometric probability theory who has also worked with Sylvester), but the one we refer to is:

Let $S$ be a region with measure (e.g., 2d area) $s$ and boundary $\partial S$. If $H$ is an event which depends on the positions of $n$ random points $p_1, \dots, p_n$ in $S$. Then

$$\partial\prob{H} = \frac{n\,\partial s}{s}\nail{\prob{H \mid p_1 \in \partial S} - \prob{H}}$$

This relates $\prob{H}$ (as a function of $s$) to the probability conditioning on one point being on the boundary. There's also a version for expected value as well as for multiple regions.

Here's a quick proof from (Solomon, 1978) Geometric Probability. Let $S'$ be a subregion of $S$ that is a teeny bit smaller than $S$; in fact, let the difference be so small that the probability of two $p_i$'s simultaneously falling in $\Delta S := S\setminus S'$ can be ignored. Let $s'$ and $\Delta s$ be the measures of $S'$ and $\Delta S$. Then

$$\begin{aligned} \prob{H} &= \prob{H \mid \text{all points}\in S'}\prob{\text{all points}\in S'} \\ &\quad + \sum_{i=1}^n \prob{H \mid p_i \in \Delta S, \text{others}\in S'}\prob{p_i \in \Delta S, \text{others}\in S'} \\ &\quad + \text{\dots ignorable terms\dots} \\ \prob{H} &= \prob{H \mid \text{all points}\in S'}\nail{\frac{s'}{s}}^n \\ &\quad + n \prob{H \mid p_1 \in \Delta S, \text{others}\in S'}\nail{\frac{s'}{s}}^{n-1}\frac{\Delta s}{s} \\ s^n \prob{H} &= \prob{H \mid \text{all points}\in S'}s'^n \\ &\quad + n \prob{H \mid p_1 \in \Delta S, \text{others}\in S'}s'^{n-1}\Delta s \\ \end{aligned}$$Plugging $s^n = (s' + \Delta s)^n \approx s'^n + ns'^{n-1}\Delta s$, we can rearrange the equation into

$$s'^n\nail{\prob{H} - \prob{H \mid \text{all}\in S'}} = n s'^{n-1}\Delta s\nail{\prob{H\mid p_1\in\Delta S,\text{others}\in S'} - \prob{H}}$$As $\Delta s$ become infinitesimal, $s' \to s$ and $\Delta S$ becomes the just boundary $\partial S$ of $S$. The theorem follows. □

Now for our 4-point problem. Let $H$ be the event that the 4 random points $A,B,C,D$ in a disk of area $s$ form a convex quadrilateral. Crofton's theorem gives

$$\partial\prob{H} = \frac{4\,\partial s}{s}\nail{\prob{H \mid A \in \partial S} - \prob{H}}$$The size of the disk doesn't really affect $P(H)$, meaning $P(H)$ is a constant w.r.t. $s$ and thus $\partial \prob{H}/\partial s = 0$. So we get $\prob{H} = \prob{H \mid A \in \partial S}$, meaning pinning $A$ on the boundary does not change the answer. Our final answer is

$$\begin{aligned} \prob{H} &= \prob{H \mid A \in \partial S} \\ &= 1 - \prob{B \in \triangle ACD\mid A \in \partial S} \\ &\qquad - \prob{C \in \triangle ABD\mid A \in \partial S} \\ &\qquad - \prob{D \in \triangle ABC\mid A \in \partial S} \\ &= 1 - 3\prob{D\in \triangle ABC\mid A \in \partial S} \qquad \text{(symmetry)} \\ &= 1 - 3\frac{35/36\pi}{\pi \times 1^2} = 1 - \frac{35}{12\pi^2} \end{aligned}$$Sketches of Other Solutions

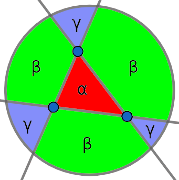

The other Putnam official solution by David Savitt (ref1, ref2) starts by extending $AB, BC, CA$ to slice the disk into 7 pieces.

Let $\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ be the expectations of the pieces (due to symmetry some pieces have the same expectation). To solve for these 3 variables we need to write 3 equations.

- The total area is $\alpha + 3\beta + 3\gamma = \pi\times 1^2$.

- Recall from the intro that the probability of 4 points forming a convex quadrilateral is $1 - 4\alpha/\pi$. But we can also start by picking $A,B,C$ first, after which $D$ must be in the green area to make the 4 points form a convex quadrilateral. Thus $1 - 4\alpha/\pi = \beta/\pi$.

- Finally, we can compute $\beta + 2\gamma$, the area cut off by the chord $AB$ that does not contain $C$. After some intense calculus, we get $\beta + 2\gamma = \frac{35+24\pi^2}{72\pi}$. We can now solve for $\alpha$.

Another solution due to Alikoski (1939) (ref1, ref2) is to solve the problem when the region is a regular $n$-gon, the answer of which is

$$1 - \frac{9\cos^2\frac{2\pi}{n} +52\cos\frac{2\pi}{n} +44}{9n^2\sin^2\frac{2\pi}{n}}$$Then take $n\to\infty$.

Yet another solution (ref1, ref2) is to cut random planes through a solid 3-dimensional unit ball. The cross section is a disk. A generalization of the other Crofton formula can relate the expected area of triangles on that cross section to other properties of the ball.

Generalization to $n \geq 4$

$\gdef\seg{\mathsf{SEG}}$

There are a few ways to generalize Sylvester's problem, such as changing the region, adding more dimensions, and adding more points. For example, (Buchta, 2009) On the Number of Vertices of the Convex Hull of Random Points in a Square and a Triangle considers $n \geq 4$ points in a triangle or a square.

Our main question for $n \geq 4$ points on a disk is answered by (Marckert, 2017) Probability that n random points in a disk are in convex position. We'll now sketch their approach.

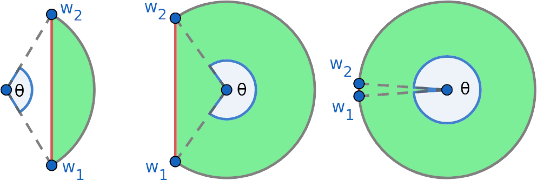

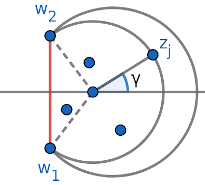

The solution will involve recursively dividing the disk into parts, so let's define $\seg(\theta, R)$ to be the segment under angle $\theta$ of a disk with radius $R$. Let's call the straight part the special border with endpoints $w_1$ and $w_2$. If points $z_1,\dots,z_n$ are randomly chosen inside $\seg(\theta, R)$, define

$$B_n(\theta) = \prob{w_1,w_2,z_1,\dots,z_n\text{ form a convex }(n+2)\text{-gon in }\seg(\theta, R)}$$And for our main question of random points $z_1,\dots,z_n$ in a full disk, we define

$$P_n = \prob{z_1,\dots,z_n\text{ form a convex }n\text{-gon in a disk}}$$From the Method 2 in Solution 2, pinning one point on the boundary does not change the probability (the paper provides an alternative argument for this). Since $\seg(\approx 2\pi, R)$ (rightmost figure) looks like having one point $w_1 \approx w_2$ on the boundary of a full disk, we can handwave (or formally prove) that

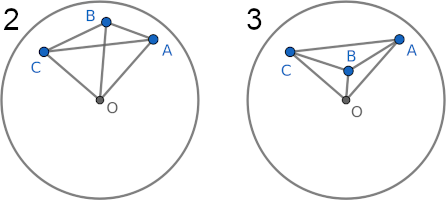

$$P_n = \lim_{\theta\to 2\pi} B_{n-1}(\theta)$$Next, we will derive a recurrence for $B_n(\theta)$. Define a family of segments $\seg(\phi, R_\phi)$ sharing the same special border with $\seg(\theta, R)$ as demonstrated below:

As we slide the center to the left, eventually the segment $\seg(\phi, R_\phi)$ will hit some point $z_j$.

Define random variables:

- $\Phi$ = the value of $\phi$ of the first such segment

- $J$ = the index of that $z_j$

- $\Gamma$ = the signed angle $\gamma$ formed by the horizontal axis, the center of $\seg(\phi, R_\phi)$, and $z_j$ (see the figure)

The distribution of $J$ is uniform. We can explicitly compute the probability density $f(\phi,\gamma)$ of $(\Phi, \Gamma)$ using a Jacobian. (Proposition 3; The result is rather hideous so we omit it here.)

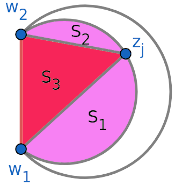

We now condition on a particular value of $(\Phi,J,\Gamma) = (\phi,j,\gamma)$. Triangle $\triangle w_1z_jw_2$ slices $\seg(\phi, R_\phi)$ into 3 parts: segment $S_1$, segment $S_2$, and triangle $S_3$. Let $k_1,k_2,k_3$ be the number of points ending up in each part ($k_1+k_2+k_3 = n-1$). The points are i.i.d. uniform within each part, and the distribution $P(k_1,k_2,k_3)$ is $\textsf{Multinomial}(n-1,\crab{S_1},\crab{S_2},\crab{S_3})$ (after scaling so that $\crab{S_1} + \crab{S_2} + \crab{S_3} = 1$).

For all the points $w_1,w_2,z_1,\dots,z_n$ to form a convex $(n+2)$-gon:

- No points should be in $S_3$ (i.e., $k_3 = 0$).

- The $k_1$ points in segment $S_1$, along with $w_1$ and $z_j$, should form a convex $(k_1+2)$-gon.

- The $k_2$ points in segment $S_2$, along with $w_2$ and $z_j$, should form a convex $(k_2+2)$-gon.

This leads to a recurrence of the form

$$ \prob{\text{convex}\mid \phi,\gamma} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1}\prob{k_1=k,k_2=n-1-k,k_3=0}B_k(\dots)B_{n-1-k}(\dots) $$(where the angles in $\dots$ depend on $\phi$ and $\gamma$) and the final recurrence is

$$ B_n(\theta) = \int_0^\theta\int_{-\phi/2}^{\phi/2}\prob{\text{convex}\mid \phi,\gamma}f(\phi,\gamma)\,d\gamma\,d\phi $$Unfortunately, there is no closed form that works for all $n$, and the integrals can become quite nasty even for a computer. The paper computes $P_n$ for some small $n$'s such as $P_5 = 1 - 305/48\pi^2$.

References

- Sylvester's Four-Point Problem: Wolfram MathWorld

- Disk Triangle Picking: Wolfram MathWorld

- Putnam 2006 and solutions

- Expected area of triangle formed by three random points inside unit circle: Math StackExchange

- (Buchta, 2009) On the Number of Vertices of the Convex Hull of Random Points in a Square and a Triangle

- (Calka, Stochastic Geometry 2019) Some Classical Problems in Random Geometry

- (Marckert, Braz. J. Probab. Stat. 2017) Probability that n random points in a disk are in convex position

- (Pfiefer, Mathematics Magazine, Dec 1989.) The Historical Development of J. J. Sylvester's Four Point Problem

- (Sharpe, arXiv 2021) Random Hyperplanes of a Convex Body, Sylvester's Problem and Crofton's Formula

- (Solomon, 1978) Geometric Probability

- (Woolhouse, Mathematical Questions with Their Solutions from the Educational Times, Vol. 7., 1867) Some Additional Observations on the Four-Point Problem